Please enjoy this encore post on SFF movies with adult lessons, originally published April 2016.

When you’re a kid, the adult world is filled with mysteries. Adults talk about things that are literally and figuratively over your head. If the news comes on, you’ll catch fragments of conflicts that don’t make any sense. If you happen across films or books for adults, there might be scenes that baffle you, since you lack the context.

Sometimes the best way, or even the only way, to understand these huge ideas is through movies. Why don’t people want to live in a shiny new building? What is “light speed”? And how can responsibility ever be fun? Emily and I rounded up a few movies that helped us figure out these huge concepts when we were kids.

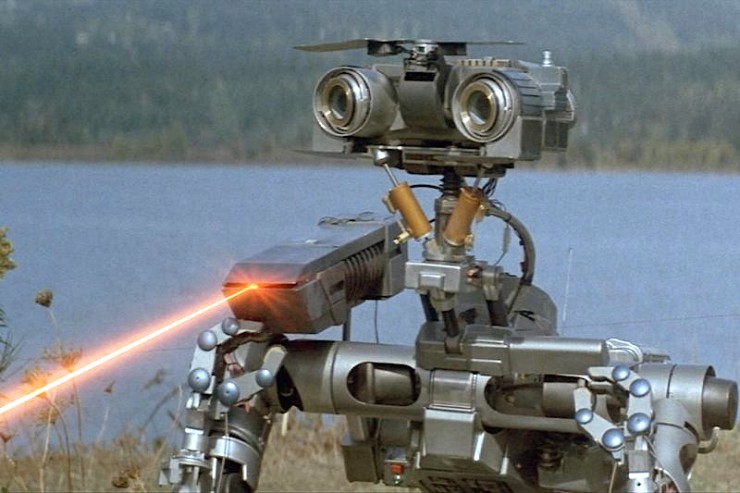

What’s the Big Deal With Free Will? – Short Circuit

Leah: Sure, Number 5 is alive, but what does that truly mean? How did he obtain sentience? Was it the lightning bolt? Divine intervention? Purest Hollywood magic? If not even Steve Gutenberg and Ally Sheedy know, how can we hope to? What we can know is that as soon as Number 5 achieves consciousness, he learns to fear its absence. “NO DISASSEMBLE!” he wails, crying against the dying of the light. He becomes hungry for knowledge, and requires INPUT, because devouring facts, mastering knowledge, and gaining a new understanding of the world around him helps him to feel powerful. Permanent. Yet he learns in the end that all the knowledge in the world does not grant one wisdom, and risks disassembly in a desperate bid to help his human companions. And thus he learns that the very fleeting nature of consciousness is what gives it its value. Only once he’s understood this is he able to claim his identity, and name himself.

Who’s Johnny? We are all Johnny.

Light Speed and the Flexibility of Time – Flight of the Navigator

Emily: The true heart of Flight of the Navigator is ultimately about family and belonging, but there’s also an attempt to explain certain basic scientific concepts to children. When David heads home after a brief bout of unconsciousness in the forest, he discovers that eight years have passed even though he has stayed the same age. While he’s under the watchful eye of NASA, a computer extracts answers from David’s mind about his whereabouts during those eight years. It turns out that he was “in analysis mode on Phaelon,” a planet light years from Earth.

In one of the few points of the film where anyone bothers to explain things calmly and carefully to David, Dr. Faraday tells the boy that if the ship he was taken by was capable of traveling at light speed, then that would explain why he hasn’t aged. The passage of time slows down as you get closer to light speed, so even though eight years passed on Earth, the light-speed-traveling David only aged a few hours. Seeing the still-young David return to a much older world instantly gave me a simple working knowledge of light speed.

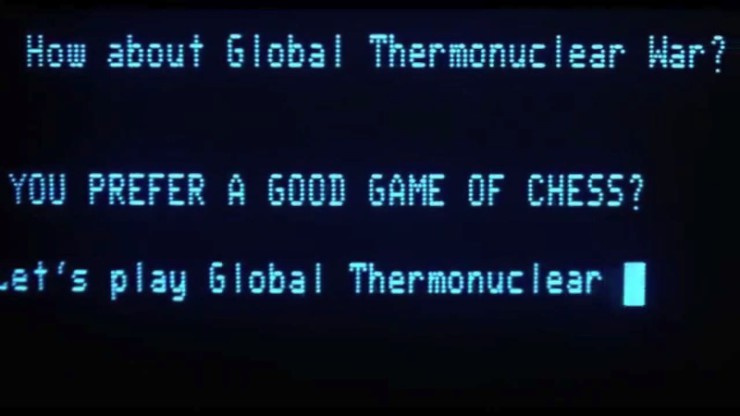

What Was “The Cold War”? WHAT? Seriously? – Wargames

Leah: The Cold War was a terrifying period in U.S. and Soviet history, and now that we’re a few decades beyond it, the whole situation seems even more unreal. We were just on the brink of a global apocalypse? For years? And everyone agreed to live that way, and all the other countries just had to wait, and hope that Nixon and Brezhnev didn’t get into an argument? Wargames gives an easy way to explain this period to today’s kids, with the more current lesson of internet caution.

High school student David Lightman meets a mystery friend on the early internet, and agrees to play a game with them. Of the options, which include chess and backgammon, David makes the admirably snarky but monumentally dumb choice of “Global Thermonuclear War.” Unfortunately, his new friend is a computer specifically programmed to go through with declarations of war that humans find too difficult. David and his friend Jennifer spend the rest of the movie trying to reason with the computer, named WOPR, learning along the way that the Cold War is absurd. In the chilling final sequence David has to teach the computer that there’s no winning strategy in a nuclear war, which is a little on-the-nose, but certainly an effective way to explain the political climate of the 1950s-1980s to children.

There is also the even more chilling message that it’s the adults in the room, not the internet-using kids, who happily signed away free will by allowing a computer to decide the fate of humanity.

Responsibility is Not a Terrible Thing – Labyrinth

Emily: There are so many excellent messages that can be taken away from Labyrinth, but when you’re a kid, the one that registers clearest is likely Sarah’s acceptance of responsibility. Regardless of Jareth’s true place in narrative (and in Sarah’s psyche), the plot is ultimately kicked off by her desire to ignore her baby half-brother Toby in favor of playing make believe games. The labyrinth itself is a lesson to Sarah in shirking her responsibilities. By wishing her brother away, she has to work much harder to get him back than she ever would have if she’d simply done her babysitting duty, and let her dad and stepmother have a date night.

Several of the labyrinth’s lessons are designed to bring Sarah to this conclusion. Her insistence that the labyrinth’s tricks are “not fair” is met with sneers and rebuttals all around. Sarah has to learn that life isn’t always fair, and people simply have to deal with that reality. Then she gets a lesson in selfishness when she eats a drugged peach offered up by Hoggle without offering any of it to her other friends, who are also hungry; this drops her into a sexy ballroom sequence that costs her time. And finally, Sarah is confronted with all her possessions in the labyrinth’s junkyard, and comes to the realization that all of her belongings are basically meaningless–her brother matters much more. After absorbing these truths, and many more, Sarah is able to solve the labyrinth and get her brother back, discovering that responsibility isn’t such a terrible thing after all.

Greed Destroys Communities – Batteries Not Included

Leah: In Batteries Not Included, (which was co-written by Brad Bird, by the way) tiny spaceships fly down to help the residents of a run-down East Village apartment that is being threatened by a rich developer. The ships themselves are both sentient and extremely handy, and use their superior tech to help the building’s residents to save their home. The building’s eclectic residents include a poor artist, a single mom, and an elderly woman living with dementia, and are all presented as real humans compared to the developers, who are heartless—and occasionally nearly murderous.

The film is solidly on the side of the tenants, and the small, vibrant community they’re trying to salvage. As a kid watching the movie, I liked the cute robots, but I also liked new, shiny things. I loved skyscrapers, sleek cars, and any trappings that implied a solid, upper-middle-class existence. At first I found the dusty tenement off-putting, and I was unsettled by Jessica Tandy’s dementia-addled landlady. As the movie went on, though, I began to feel more and more empathy for the people who were being displaced. By the end I had accepted the message that I believe today: greed sucks.

Acceptance of the Other – E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

Leah: This one might be a little obvious. While E.T.‘s more overt message was that life goes on after a divorce, and some families are not nuclear, and that’s okay…, E.T. the character is basically an accidental illegal immigrant. He means Elliot and America no harm, and he’s happy to use his skills and technology to help people.

Unfortunately, many people’s first response is to view him with fear and suspicion. Said fear damn near kills him, but he finally recovers. If the government that hunted him down has been more empathetic, and, y’know, just talked to E.T., he probably would have shared his healing mojo with them, and quite possibly even put Earth in communication with his world, which is just teeming with super-advanced wrinkly alien scientists. Instead, they traumatized a bunch of innocent people, threatened children with guns, and forced E.T. to flee back home forever.

E.T. added to the fairly strong “adults are not always right” messages I was already getting from movies, with a healthy dose of “sometimes the government is off-base, too.” Not only did it prepare me to live in a modern world that is about 98% political spin, but it also prepped me for my intense X-Files fandom. Thanks, Mr. Spielberg!

Empathy and Environmentalism – The Dark Crystal

Emily: The world that The Dark Crystal depicts is dying, bound up in a prolonged state of decay. As Kira and Jen work to restore the Dark Crystal to its whole state, we watch the Mystics make a journey to the palace and merge with Skeksis to re-become the urSkeks. Kira is hurt in this fight, and one urSkek named the Historian advises Jen: “Hold her to you, for she is a part of you, as we are all a part of each other.” He then revives Kira as the world blooms to life. This theme of interconnectedness runs throughout the film, and the idea that healing the world comes with sacrifice is also embedded in the narrative.

Don’t Be Afraid of Your Dark Side – The Dark Crystal

Leah: If you thought the Mystics were the good guys, and Skeksis were pure evil… it’s a lot more complicated than that. They’re complementary halves of a whole personality, and they have to balance each other. Just like how, if you’re prone to anger or depression, you need to accept that and find a way to work with your brain, since if you just try to bury that part of you you’re going to snap.

We knew all those hours in front of the TV were worth it. Now that we’ve told you some of our favorite life lessons, we want to hear about yours! What movie opened your little-kid eyes to some adult-sized truth?